Fascia 101: What is fascia?

Most fitness instructors talk about stretching, toning, and building muscles and protecting joints. Do we only exercise muscles? It might sound silly, but have you never wondered how do our muscles not slide off the bones when we move? How do our organs not move around when we jump and run? What gives our body structure? It cannot just be the muscles and bones. That is when fascia comes into the picture.

What is fascia?

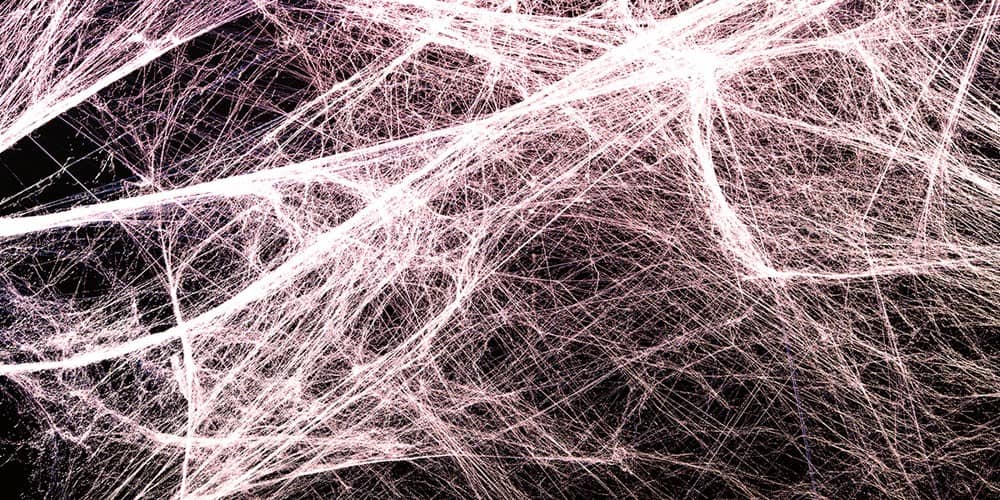

Fascia is the biological fabric that holds us together. It is the connective tissue network that surrounds and holds every organ, blood vessel, bone, nerve fibre and muscle in place. You are made up of about 70 trillion cells and 70% of it contains water. It is this fascia, which is the three-dimensional web of fibres, a gooey gel and protein cells that binds them together.

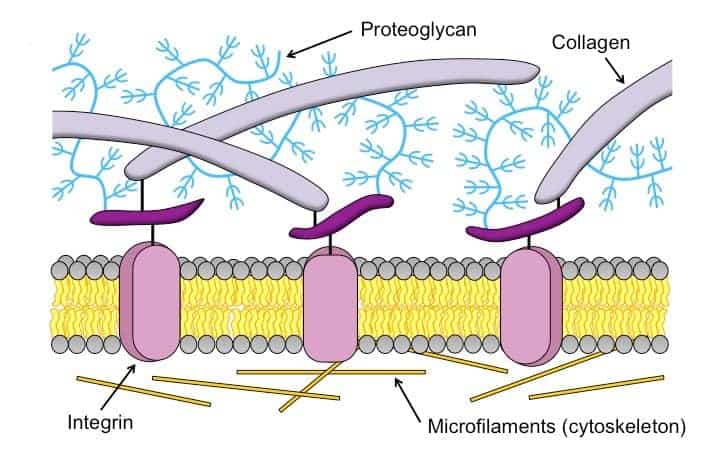

Traditionally, in medical terminology, fascia was used by surgeons to describe the dissectible tissue seen in the body encasing other organs, muscles and bones like the thoracolumbar fascia or the fascia lata. However, recent scientific research has widened the definition to include all collagenous soft tissues in the body, including the cells that create and maintain extra cellular matrix. Thus, everything from tendons, ligaments, bursae, aponeurosis, to endomysium, perimysium and epimysium come under the umbrella of fascial tissues of the human body.

Imagine the fascia to be like an onion. When you look at it from the outside, it looks like a single entity. But when slice it vertically into two, you can see the layers and layers of it inside. Similarly, fascia has multiple layers.

Fascia can be classified as superficial, deep, parietal, or visceral and further classified according to anatomical location. Superficial fascia is found in the subcutis (below the skin). Deep fascia is the dense fibrous connective tissue that interpenetrates and surrounds the muscles, bones, nerves, and blood vessels of the body. Parietal fascia is what surrounds organs. Visceral fascia belongs the organs and is found within their cavities.

Function

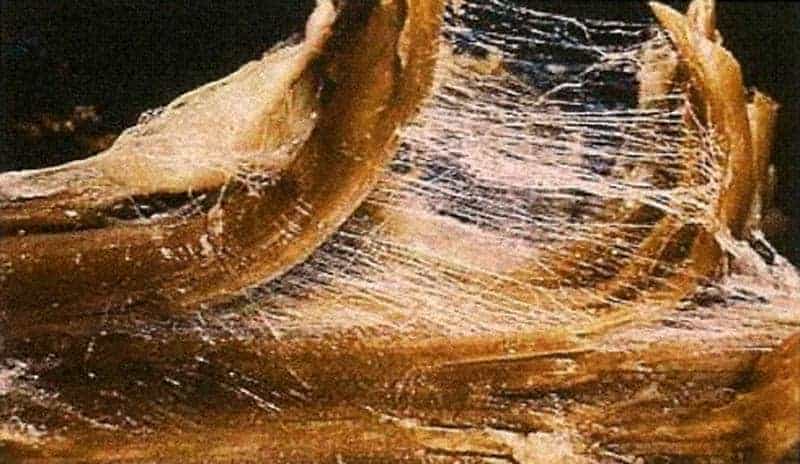

Fascia may appear passive structurally but is, in fact, active. Fascial tissue stabilizes, encloses and separates internal organs and prevents friction between bodily structures during movement, enabling them to move smoothly against each other.

Each layer comprises of closely packed bundles of collagen fibres and a gel like substance known as the extra-cellular matrix. In muscles, these fibres can bend in a wavy pattern parallel to the direction of pull and are designed to stretch as you move. It has a variable degree of elasticity that allows it to withstand deformation when forces and pressure are applied as it can recover and return to its starting shape and size.

Fascia is one of the richest sensory organs in our body, embedded with nerve endings and mechanoreceptors. It plays a major role in perception of posture and movement affecting our proprioception and coordination. Whenever we change our posture or move in any way, mechanoreceptors in the fascia deform and activate, sending information to the nervous system.

Dysfunction

Healthy fascia is smooth, slippery and flexible. When it becomes thick, crinkly and gummy, it is a cause for concern. When lengthened beyond its limit is distorts and can be subjected to tearing. If loaded constantly over a prolonged period, deformation can occur making it hard and less fluid. When our fascial system is not functioning as optimally as it should, it can manifest as tightness and pain, restricting our movement and making it painful to maintain good posture when we are sitting, standing, walking or running.

Fascial dysfunction can occur due to a variety of reasons. Lack of movement variations, sub-optimal nutrition, inflammation, surgery, habitual posture and trauma can impact the fascia’s ability to glide and slide, which normally helps the distribution and transmission of tension across the body. Compensatory movements can then occur resulting in more stress on the fascial system.

Compartment syndrome is one such dysfunction in which the fascia does not stretch, leading to increased pressure on the capillaries, nerves, and muscles in the compartment. As a result, blood flow to muscles and nerve cells is disrupted. Without a steady supply of oxygen and nutrients, these cells can be damaged.

Conclusion

Our body compensates for a lot of tightness and restrictions in movement, but if overlooked for a very long time, fascial dysfunction can cause multiple problems. The first step is understanding our body beyond the traditional musculoskeletal system. We are conducting a series of workshops on the Wonder of Anatomy and Movement. You can join the fascia series to learn how we can keep our fascia healthy. Whether you are a movement instructor, physical therapist, or even any other allied medical professional, your clients will benefit from this in-depth knowledge of the myofascial web. Sign up here.