Basics of Anatomy: Hip Joint

It is said that one discovery transformed the course of humanity. It made us from agile hunter-gatherers to farmers and later chefs. That discovery was fire. Fire transformed not only our diet but also modified our movements. We didn’t need to run to catch prey or climb trees to get nuts and fruits. A lot of our activities now required sitting. And with every generation, the need to use our lower limbs has reduced. But that hasn’t changed the anatomy of our body nor that of our hip joint, which remains the most stable joints of our body. It bears the weight of our torso and head on our legs, when we sit, stand, walk, or run. However, with increased sedentary postures, there can be an early onset of dysfunctions in the joint. Read on to understand your hip joint and how you can keep it healthy.

Anatomy

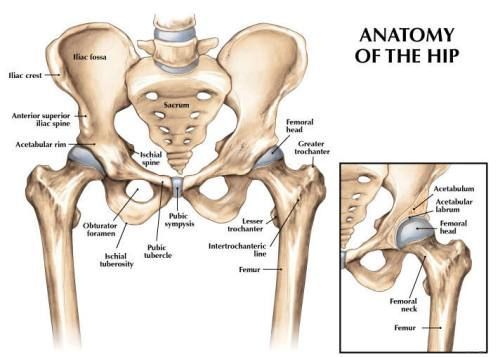

The Hip Joint is a ball and socket synovial joint, formed by an articulation between the acetabulum of the pelvis and the head of the femur or thigh bone. It forms a connection from the lower limb to the pelvic girdle. The entire weight of the upper body is transmitted through this joint to the lower limbs during standing. Thus, the hip joint is the most stable joint in the human body.

As the primary function of the hip joint is to weight-bear, it compromises mobility for stability as opposed to the shoulder joint. It is almost impossible to dislocate this joint. There are a number of factors that act to increase the stability of the joint.

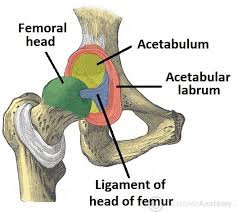

The first is the acetabulum which is a cup-like depression located on the inferior-lateral aspect of the pelvis. It is formed by the fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubic bones which make up the pelvis. The head of the femur is hemispherical and fits completely into the concavity of the acetabulum. Both the acetabulum and head of the femur are covered in articular cartilage which is thicker at the places of weight-bearing. Its cavity is deepened by the presence of a fibrocartilaginous collar- the acetabular labrum, which is the second factor increasing the stability of the joint.

The third factor is the ligaments. The iliofemoral, pubofemoral and ischiofemoral ligaments (which go from three parts of the pelvis to the femur) are very strong and along with the thickened joint capsule, provide a large degree of stability. These ligaments have a unique spiral orientation which causes them to become tighter when the joint is extended.

In addition, the muscles and ligaments work in a reciprocal fashion at the hip joint. Anteriorly, where the ligaments are strongest, where there the groin muscles are fewer and weaker. Posteriorly, it is vice versa. They effectively ‘pull’ the head of the femur into the acetabulum by balancing each other out. This is further reinforced by the capsule of the hip joint which surrounds it almost completely.

Function

Being a ball and socket joint, the hip joint permits flexion and extension (forward and backward movement), abduction and adduction (sideways), external rotation-internal rotation, and circumduction. However, the range of motion is quite restricted as compared to the shoulder joint.

The main flexors of the hip joint are the iliopsoas muscle (psoas major and iliacus) and the rectus femoris muscle (part of the quadriceps). A main part of iliopsoas is to stabilise. This stability is enhanced by hamstrings (back of the thigh).

The primary extensor of the hip joint is the gluteus maximus muscle, assisted by the hamstring muscles. This movement of our leg backward in the hip joint is limited to 30 degrees due to the ligaments and the bony structure.

The primary abductors of the hip joint are the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus muscles, assisted by the tensor fasciae latae, piriformis, and sartorius muscles. The major adductors of the hip joint are assisted by the gluteus maximus. The adductors and abductors balance each other to keep the pelvis stable and aligned over the hip joint. The hip abductors play an active role in stabilizing the pelvis during specific phases of the gait cycle.

The anterior fibres of glutei minimus and medius are the principal muscles responsible for internal rotation of the hip joint. These muscles are assisted by the tensor fasciae latae and most adductor muscles. External rotation is produced by the gluteus maximus together with a group of 6 small muscles called the deep lateral rotators. Internal and external rotation of the hip joint occurs along an axis that runs from the head of the femur to its condyles. Rotation also causes the toes to point in and out.

Human anatomy is truly beautiful as it doesn’t compromise function. It is fascinating how the range of motion of rotation and adduction-abduction changes when the hip joint is flexed than extended. This allows us to walk and run and do various functions with our lower limbs. There is more stability in function. Especially in the gait cycle keeping it sturdy.

Dysfunction

Dysfunction in the hip is often due to developmental conditions, injuries or infections.

One of the most common dysfunctions is osteoarthritis in old age. As discussed in our previous blog on osteoarthritis, wear and tear of the cartilage joint results in inflammation and pain. Overuse can occur as a result of stiffness in the lower spine and thus more movement in the hip joint. Also, if the hamstring is tight, especially in men, the movement in the hip joint is also restricted, which causes stiffness and pain. Osteoarthritis restricts rotation and abduction in most people later on in life. If it gets worse, hip replacement surgery is done.

Another hip disorder is Young hip pain. This causes impingement of the joint capsule anteriorly. Also known as femoral acetabular impingement (FAI) it is caused by the looseness or weakness in the deep hip flexor and hip rotator muscles. The ball of the femur glides anteriorly leading to the pinching in the front. This condition makes bending the knee painful, especially in movements like running.

Sedentary postures can provoke osteoarthritic changes early on in life. Irrespective of whether you have pain or no, it important to keep the joints healthy. To avoid dysfunction in the hip joint, it is necessary to maintain good alignment in the spine and knee. Correction of the posture of the lower back and strengthening of muscles in and around the hip joint, like in Pilates, can help control the excessive wear and tear in the joint.

Pilates for the Hip Joint

Since the hip joint is highly stable, we work on maintaining mobility in the joint, while also working on the stability of the lower spine as they are inextricably linked. The following exercises help to strengthen the hip muscles while keeping the spine neutral.

Clam with theraband

Toy Soldier with scissors on ball

Bent knee open close in tabletop

Sitting is the new smoking: we have heard this a lot of times. But it is true, we have to keep the hip joint mobile. We need to be agile on our feet. And to do that we need to keep our hip joint mobile. Walking is the simplest exercise you can do to keep your lower limbs active. And while you are at it, do some Pilates to make them stronger. As you will lose it if you don’t use it! And you really don’t want to lose your ability to explore the world on your own two feet!

To learn more about the different joints and the anatomy of our body, check out the Wonders of Anatomy Workshops.

This blog is written under the guidance of Dr. Persis Elavia.